The characters in this session were:

- Alabastor Quan, a gnome rogue-turned-warlock and failed circus ringmaster; wielder of a cursed dagger and member of the Ravenswing Thieves’ Guild.

- Armand Percival Reginald Francois Eustace de la Marche III, a suspiciously pale, apparently human noble and sorcerer, and certainly not a ghoul (how dare such a thing be suggested).

- Caulis, a homunculus warlock liberated from its master; has made a pact with certain Faerie Powers.

- Comet the Unlucky, waspkin ranger, a dreamer and an idealist, longing for the restoration of the Elder Trees and the liberation of his people. Loathes the Harvester’s Guild, parasites and destroyers.

- Garvin Otherwise, a human rogue and burglar of the Ravenswing Thieves’ Guild, with a very, very peculiar past and a zoog pet, Lenore.

- Miri, trollblood wizard, plucked from Mount Shudder and raised amongst Hex’s arcane elites. A recent graduate of Fiend’s College.

- An ancient and enigmatic Lengian cleric of the Mother of Spiders, name unknown. She wears bulky ecclesiastical garments covering an uncertain number of limbs and goes by “Sister.”

XP Awarded: 1200 XP

The party was reeling in the wake of a sinister discovery: someone had been deliberately tormenting Genial Jack, apparently in an effort to produce tidal waves to weaken Hex, and this same individual or individuals might be the ones behind the Harrowgast that had plunged Hex into an endless winter with the aid of the trollblood clans to the north. A secret order of Lengian assassins had been their catspaw this time – but who was the mysterious “S” who, twice now, had been implicated behind the two otherwise disconnected schemes? Was it some traitor to the city within Hex – or one of its many foreign rivals?

After conferring with the High Navigators of Jackburg, the party decided that the Hexad Council – the executive government of Hex, elected by its magical citizenry to the highest offices of the land – must be alerted of this mysterious and sinister threat. Still, there were some misgivings concerning individual council members.

“Silas Thamiel was aggressive when it came to Troll Country,” Alabastor pointed out. The group was on their way back to Hex, in a small ferry conveying travelers between Jackburg and the City of Secrets. Waves lapped at the side of the boat as the group drank hot tea and rum in a quiet corner.

“And Arabella Sickle wasn’t exactly our biggest fan,” Garvin agreed. “I wonder… her last name is ‘S’.”

“Not exactly hard proof,” Miri pointed out.

“We should be cautious,” Sister said. “Tell them what they need to know.”

“Do they know about Melchior and the Organon?” Comet asked, good-naturedly.

“They’ve definitely don’t, and we’d like to keep it that way,” Armand insisted, with faint irritation. “So keep quiet about anything pertaining to the Books, to the Hive of the Thirteenth Queen, anything of that nature.”

Caulis studied its newly acquired shrunken head, stolen from the Cuttlethieves. “I have an idea,” it said. “This head… the head of Granny Midnight. It can be used to listen in on people. You whisper their name into her ear and she speaks with their voice. After we meet with the Council, we could, you know. Whisper one of their names in her ear. Listen in on what they talk about.”

There was some discussion about the safety of this plan, but the group resolved to follow through with it after their meeting with the Council, with High Navigator Quell accompanying them. Getting off the ferry at the foggy district of Caulchurch, they took Tonsil Boulevard up to Enigma Heap and made their way through the looming structures of the Old City to the Hall of the Hexad Council.

They announced themselves at the gates of the Council to the gigantic golems that stood guard, insisting that their business was both pressing and secret. After a bit of persuasion – assisted by Alabastor’s silver tongue – the guards relented, and the group entered the Hexad Council chamber, interrupting what seemed an intense argument over repairs to the docklands following the small tidal waves caused by Genial Jack’s nightmares.

They announced themselves at the gates of the Council to the gigantic golems that stood guard, insisting that their business was both pressing and secret. After a bit of persuasion – assisted by Alabastor’s silver tongue – the guards relented, and the group entered the Hexad Council chamber, interrupting what seemed an intense argument over repairs to the docklands following the small tidal waves caused by Genial Jack’s nightmares.

“Pardon the interruption,” Alabastor said. “But we have important news.”

Quickly, Parthenia Quell and the party-members quickly summarized recent events for the Council.

Silas Thamiel – stern, scarred, and authoritative – looked down at the party with concern.

“If a conspiracy is afoot, it may well be that some foreign power is behind it. Hex has many enemies. It may be wise to dispatch the Warders to begin seeking them out. Perhaps a Committee for Hexian Security should be formed, to defend us against these insidious forces.”

“If a conspiracy is afoot, it may well be that some foreign power is behind it. Hex has many enemies. It may be wise to dispatch the Warders to begin seeking them out. Perhaps a Committee for Hexian Security should be formed, to defend us against these insidious forces.”

A murmur of agreement rippled through the Council. Garvin, ever observant, noted that Silas looked unusually haggard, dark circles under his eyes, which twitched occasionally as from lack of sleep or some other vexation.

Next to speak was Arabella Sickle, whose normally haughty posture was tempered by what seemed grudging respect.

“I must admit to having my doubts as to your capabilities. But it seems as if disaster has been neatly averted, with the blessing of the Navigators. This Council’s trust in you was not misplaced. I am disturbed, however, by your description of this Lengian, a worshipper of Icelus. Hex values freedom of belief, but the powers of this order openly violate another freedom – freedom from psychic violation. The mind is sacrosanct.”

“I must admit to having my doubts as to your capabilities. But it seems as if disaster has been neatly averted, with the blessing of the Navigators. This Council’s trust in you was not misplaced. I am disturbed, however, by your description of this Lengian, a worshipper of Icelus. Hex values freedom of belief, but the powers of this order openly violate another freedom – freedom from psychic violation. The mind is sacrosanct.”

She looked to Sister.

“You are a Lengian priestess, and a loyal citizen of Hex. To be blunt, I trust your loyalty more than that of the Matriarchs of Cobweb Cliffs. Were we to appoint an external Inquisitor from the Warders or another church, the Lengians would never accept them. But if we were to appoint you an Inquisitor, charged with rooting out heretics worshipping this Icelus, how would the Lengians react?”

Sister looked deeply uncomfortable, but considered the proposition. “It would be… a delicate process. The Matriarchs would not be pleased, but… I might be able to convince them of the necessity of action. The Order of Icelus are deeply heretical. Still… to become ‘Inquisitor’ does not precisely sit right with me…”

Arabella smirked. “Then I am afraid we will have to instruct the Warders to take action, possibly even establish a more permanent presence in Cobweb Cliffs. I fear difficult times ahead for your people…”

Sister bristled, conferring briefly with her companions

“Very well. I’ll be your Inquisitor, but I will require autonomy and trust. I will report to the Council, but I am not your minion. I will seek out these cultists of Icelus, but I will do it my own way, and using my own methods.”

The Infernal Archbishop smiled. “Very good. I hereby move to grant the Lengian known as ‘Sister’ the position of the Hexad Council’s Inquisitor. All in favour?”

A vote proceeded, with Silas, Valentina, and Barnabas voting in favour, and Iris and a half-slumbering Angus abstaining. The motion carried; Sister was elevated to the rank of Inquisitor. With swift magic, a suitable symbol of office in the form of a gilded six-sided web was conjured, to be worn about the neck.

Iris – currently violet-haired – adjusted her spectacles thoughtfully. She seemed anxious.

“I agree with my colleagues that these reports are disturbing, and I share their concern for the city’s well-being. However, I am concerned that if we involve the Warders directly in further investigations, the conspirators may be alerted and slip free before we can find them. I suggest we consult with the Institute of Omens, and the Soothsayers of Saint Monstrum’s Cathedral. They may be able to use divination to produce some clue as to the identity of the conspirators. In the meantime, I suggest we entrust the Variegated Company with further inquiries, and grant them acting Special Investigator status, reporting strictly to this Council.”

“I agree with my colleagues that these reports are disturbing, and I share their concern for the city’s well-being. However, I am concerned that if we involve the Warders directly in further investigations, the conspirators may be alerted and slip free before we can find them. I suggest we consult with the Institute of Omens, and the Soothsayers of Saint Monstrum’s Cathedral. They may be able to use divination to produce some clue as to the identity of the conspirators. In the meantime, I suggest we entrust the Variegated Company with further inquiries, and grant them acting Special Investigator status, reporting strictly to this Council.”

The Company conferred amongst themselves, and presently agreed to this larger task as well.

Barnabas – plump, intelligent, appraising – fidgeted in his seat.

Barnabas – plump, intelligent, appraising – fidgeted in his seat.

“Who stands the most to gain from this sort of destructive activity?” he asked. “The trollbloods I can understand… you can’t expect such primitives to comprehend the finer points of geopolitics.”

Here, a newly-educated Alabastor winced, while Miri gritted her teeth.

“Ah, present company excepted,” Baranabas said hurriedly, with a glance at the seething trollblood wizard. “But whoever is behind this is more than some savage with a grudge. What do you think the conspirators are trying to accomplish?”

“I have no specific reason to suspect their involvement,” Garvin said, thinking of his sojourns to the alternate reality where vampires ruled the city. “But is it not known that the Sanguine Lords and Ladies have long coveted the knowledge of the Old City? Might this be the work of Erubescence and the Red Realm?”

Barnabas stroked his beard. “Perhaps. Certainly the subtlety of this scheme brings to mind the vampires. But they are historically no friend of the trollbloods…”

“The Night Queen has always seen Genial Jack as an equal,” Parthenia put in. “Unless her thinking has altered in some fundamental way, I cannot imagine her wishing him ill.”

“The Night Queen has always seen Genial Jack as an equal,” Parthenia put in. “Unless her thinking has altered in some fundamental way, I cannot imagine her wishing him ill.”

“Could it be Teratopolis, out for vengeance against Hex?” Caulis put in. “We did… you know… turn them all into horrible mutants.”

Iris shook her head. “It is possible, of course, but we have been making strides with Teratopolis. Trade has increased between our realms. It feels as if we are finally putting the War of Miscreation behind us.”

“I wonder if Jack himself may be helpful,” Angus mused. “Could this assassin, or another like him, not try to target him again?”

“We are taking steps to ward Jack’s mind against intrusion,” Parthenia said. “And, using the ritual the Company provided, we can guard his dreams directly.”

“Yes, this ritual!” Valentina said, having been silent the whole meeting. “Where did you find it?”

“Yes, this ritual!” Valentina said, having been silent the whole meeting. “Where did you find it?”

Armand interjected, reluctant to disclose the party’s possession of the legendary Oneironomicon.

“A, ah, spell we discovered in the Old City,” he half-lied.

“I see,” the rumoured lich in the guise of a young girl said. “I would be very interested in seeing this spell, when it is convenient. But I digress – you have work to do, Special Investigators. Unless my colleagues have further questions?”

There was an exchange of looks, but the Council agreed to bring the meeting to a close. The newly empowered Company departed the Hall of the Hexad Council, making for Armand’s nearby townhouse. High Navigator Parenthenia Quell returned to Jack, shaking hands with Sister and thanking the group again before leaving.

“Well, that went differently than I thought!” Comet said, proud of his new status. “The Order better watch it!”

“Something was off in there,” Garvin put in. “That was too easy.”

The party was heading down Nightmare Alley towards Fever Lane when Garvin’s highly cultivated thieves’ senses prickled. The party was being followed by two figures, both swathed in heavy clothing

“We’re being followed,” the thief informed his companions.

“I’ll send Eleyin to take a closer look,” Caulis said, sending the psuedodragon familiar to spy on the strange pair. One was a short, fat figure, in a black frock coat with a huge slouch hat shadowing their features, the other, tall and thin, a grey gown swathing her skeletal frame. The little figure walked with a walking stick topped by a cat’s skull. The homunculus reported back what it had seen through the familiar’s eyes.

“I’ll send Eleyin to take a closer look,” Caulis said, sending the psuedodragon familiar to spy on the strange pair. One was a short, fat figure, in a black frock coat with a huge slouch hat shadowing their features, the other, tall and thin, a grey gown swathing her skeletal frame. The little figure walked with a walking stick topped by a cat’s skull. The homunculus reported back what it had seen through the familiar’s eyes.

“I have an idea!” Comet said. “Down here!” He buzzed down a side-street, gesturing that the party follow. Sister, meanwhile cast Pass Without Trace, and the group concealed themselves in the shadows of doorways and behind pillars along the street’s length.

Hoarse, uncanny laughter echoed down the empty street . The thin woman in the grey dress waltzed out of the shadows, grinning with yellow teeth.

“Now where did the little dearies go?” she asked. “Did you see, Monsieur Gobble?”

Soft foot-falls slapped the pavement as a round shape in black bounced out of the darkness.

“They must be here somewhere, Madame Slake,” the second stranger said, toying with his walking stick. “Naughty little alley-rats skulking in the shadows. And what must we do with alley-rats?”

“Why, Monsieur Gobble, we catch them in a trap,” Slake declared. Her grin began to widen, and suddenly proboscii juddered from her palms like obscene knives, a pair of mosquito wings sprouting from her back. Monsieur Gobble doffed his cap, revealing a grotesque second mouth gaping at the top of his skull, an obscene tongue tasting the air, scenting for prey…

“Why, Monsieur Gobble, we catch them in a trap,” Slake declared. Her grin began to widen, and suddenly proboscii juddered from her palms like obscene knives, a pair of mosquito wings sprouting from her back. Monsieur Gobble doffed his cap, revealing a grotesque second mouth gaping at the top of his skull, an obscene tongue tasting the air, scenting for prey…

“Demons!” Armand hissed, recognizing the interplanar interlopers as they sloughed off their mortal disguises.

Before the pair could discover them, the party leapt into action. Sister uttered a prayer to the Mother of Spiders, and instantly hundreds of spiders swarmed from the darkness, spinning webs that utterly cocooned the female demon, holding her in place. Garvin, meanwhile, fired a poisoned bolt at the male demon, even while Comet emerged from the shadows with his dancing rapier beside him, Chainbreaker in hand.

Gobble chuckled and plucked the poisoned bolt from his breast, licking the head with disgusting savour. His stomach burbled and growled, and, bouncing back, his second mouth gaped wide, and a vile stream of sulphurous vomit spewed forth, along with a veritable troupe of malformed lesser demons – like a revolting magic trick, they had emerged from his gullet, a bilious gastrointestinal conjuring.

Battle was joined, vicious and swift. Spells flew, Miri firing with two wands, Caulis and Alabastor slinging blasts of puissance, the homunculus entangling the newly spawned imps with magical vines, the gnome distracting Gobble with illusions. Comet wove through the carnage, blood spattering his magical hammer, while Armand and Sister cast from the sidelines and Garvin, flitting magically to a high balcony, continued to snipe with his crossbow.

Battle was joined, vicious and swift. Spells flew, Miri firing with two wands, Caulis and Alabastor slinging blasts of puissance, the homunculus entangling the newly spawned imps with magical vines, the gnome distracting Gobble with illusions. Comet wove through the carnage, blood spattering his magical hammer, while Armand and Sister cast from the sidelines and Garvin, flitting magically to a high balcony, continued to snipe with his crossbow.

When the dust cleared the party stood victorious, spattered with the blood of the horrid imps. Gobble had exploded in a puff of eldritch flame. Miri approached Slake, still subdued, and bent over her, wand in hand; the mosquito-demon hissed and broke a limb free from Sister’s webs, stabbing the trollblood in the neck and beginning to siphon blood from her. Miri snarled and slammed the creature’s head against the ground, ripping the proboscis from her neck and snapping it in two. Slake shrieked in agony.

“Who sent you?!” Miri snarled, as Sister wove a Zone of Truth.

“Let me leave, unharmed, and I will tell you,” Slake said, eyes glowing in the darkness.

Miri looked to her companions for assent, then back at Slake. “Agreed.”

“I do not know his name,” Slake said. “But the man who conjured us was dark of hair, weathered of complexion. Human. Tattoos ran along the left side of his face.”

“Whoa,” Comet said. “Isn’t that…?”

“Silas,” Armand said, eyes narrowing.

“What did he tell you to do?” Sister asked.

“To follow you, watch you – and, if the opportunity arose, destroy you.”

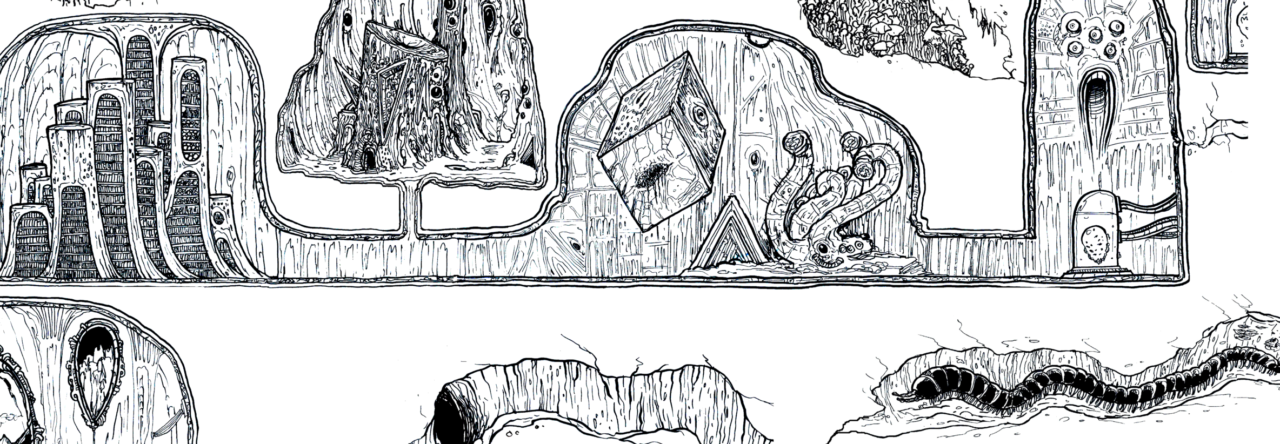

“Special Investigators.” Illustration by Bronwyn McIvor.

“Special Investigators.” Illustration by Bronwyn McIvor.

“Well, you failed there,” Miri said. “Very well. Get out of here before I change my mind.” She got up off the creature, which rose from the dissolving webs. A pair of mosquito wings emerged from her shoulders and she flitted away into the night with a curtsey.

“Come, let’s make haste,” Armand urged.

“I want to see what Granny Midnight has to say,” Caulis agreed.

The party repaired quickly to Armand’s home a few blocks away. Caulis took the withered head of Granny Midnight from its pack and whispered “Silas Thamiel” into her shriveled ears. Immediately the severed head began to speak in Silas’ voice.

“…they can be trusted with this. They have proved themselves more than capable in the past.”

There was a gap in the conversation. Quickly, Caulis whispered “Arabella Sickle” into the head’s ears.

“…agree with Silas. As I said, I have had my doubts about them, but their loyalty to Hex seems assured.”

Another gap; they tried several names, to little avail, then switched back to Silas.

“…should coordinate with the High Navigators to ensure we have a plan if the assassins break through their mental defenses, but -” Suddenly, the head ceased speaking.

“What’s wrong with it?” Comet asked, curious.

“I’m not sure,” Caulis said. “It’s like he stopped in mid-sentence.”

They listened for a time longer, and Silas continued to “cut in and out,” speaking and then suddenly not.

“I have a suspicion,” Sister said. “Perhaps Silas… is not always Silas. Perhaps something else is occasionally taking him over!”