There’s been some interest recently expressed on Discord and Google+ (before its demise – may it rest in peace) as to how I run this campaign. This is the first of a series of posts on how I approach an urban D&D game. It is, of course, not the only way to run this sort of thing – indeed, I suspect I rely rather less on a lot of common conventions for urban adventuring, most notably by eschewing procedural content-generation methods. I’m going to start by describing the kind of game I aim to run, and then I’ll talk about the procedures and techniques I use as a DM to create and sustain that game.

Urban Sandbox

Sandbox adventures frequently involve sprawling wilderness landscapes, hexcrawls, and similar structures. My goal is to take the feel of openness, freedom, and agency associated with typical sandbox play, but largely confined within the space of a single city. While some adventures have taken the characters outside of Hex (the main city in this game) to places like the wintry wastes of Troll Country, the Gothic province of Varoigne, the guts of the gigantic whale Genial Jack, and the depths of Faerie, the game is centred in and around Hex. In this sense, I am simultaneously adopting and inverting the approach of a West Marches campaign, which aims to cultivate an overarching environment, but also warns against the perils of “town adventures.” Hex is nearly all town adventure, but the town has been transformed into an adventure-worthy space.

I also DM for a large group – currently I have 10 semi-regular players. Because players come and go, skipping some sessions and attending others, the “plot lines” of the campaign are incredibly loose. There have been significant, ongoing events happening in the campaign world: Erubescence’s ambitions, the machinations of the Griefbringer, Hex’s ongoing labour struggles, a conspiracy quietly unfolding in the background which my players are now unraveling. And, likewise, there is a very rough “main quest” which the party dips into: their search for the mysterious volumes that comprise the Organon of Magic, ostensibly for the ancient archwizard and brain-in-a-jar, Master Melchior, whom much of the party actively distrust. Mostly, though, the game is a patchwork of disjointed episodes, a picaresque series of heists, vendettas, delves, and personal quests. This disjointedness is a feature, not a bug; while the players will sometimes pull on a plot thread and see where it leads, we never follow one storyline too long or too doggedly. They drive the “story” such as it is, choosing where to go, what to do, and what interests them most.

The closest literary analogues for this sort of game are Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories, as well as Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, where a cast of recurring characters are swept up in a series of adventures only loosely connected to one another. Hex has other fictional forebears – Sigil, Cörpathium, New Crobuzon, Camorr, Ashamoil – but structurally, Lankhmar and Ankh-Morpork loom largest. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories also have something of this – London in Doyle’s writing sprawls Gothic and gaslit, a labyrinth of mysteries and fog which the protagonists wander, embroiled in a disconnected sequence of macabre incidents and misadventures.

In designing Hex, I made sure to have the city open onto various other worlds and nested structures. Setting it atop an ancient, gigantic city, I made it adjacent/continuous with a megadungeon that serves as a convenient adventuring location; that dungeon is thick with impossible spaces, pocket dimensions, and portals. The idea is to present such a smorgasboard of possibilities that the players never get bored and always have a host of options as to where to go next. I want to evoke a sense of rich, infinite adventure.

Baroque DMing and Urban Space

At one point someone on Google+ (I think it was Patrick Stuart?) described what I was doing as a kind of counterrevolution. While I run a 5th edition game, philosophically I borrow a lot from old-school D&D – my game features the potential for fairly high lethality (in practice, death is pretty rare because my players are cautious), open-ended challenges, creative problem-solving, an emphasis on an immersive setting, and a prioritization of exploration and emergent storytelling over “narrative.” I prefer puzzles to “balanced” combat, out-of-the-box thinking to skill rolls, rulings to an excess of rules. The one old-school standby which I tend to eschew is procedural generation. I’m not oppposed to random tables inherently, and I do use some occasionally both of my own devising and otherwise, but I far prefer to have prepared as much as possible beforehand. The template I’m looking back to here is City State of the Invincible Overlord, where the city is entirely mapped and keyed.

In navigating the city, I want my players to feel as if nothing is being invented on the spot – the setting should feel as if it exists independently of them, and they are exploring its secrets. It should be suffused with interesting details and a sense of grandeur and verisimilitude. My goal is to produce a feeling of absorption and fascination, an experience of actually navigating a real-feeling, mind-independent space.

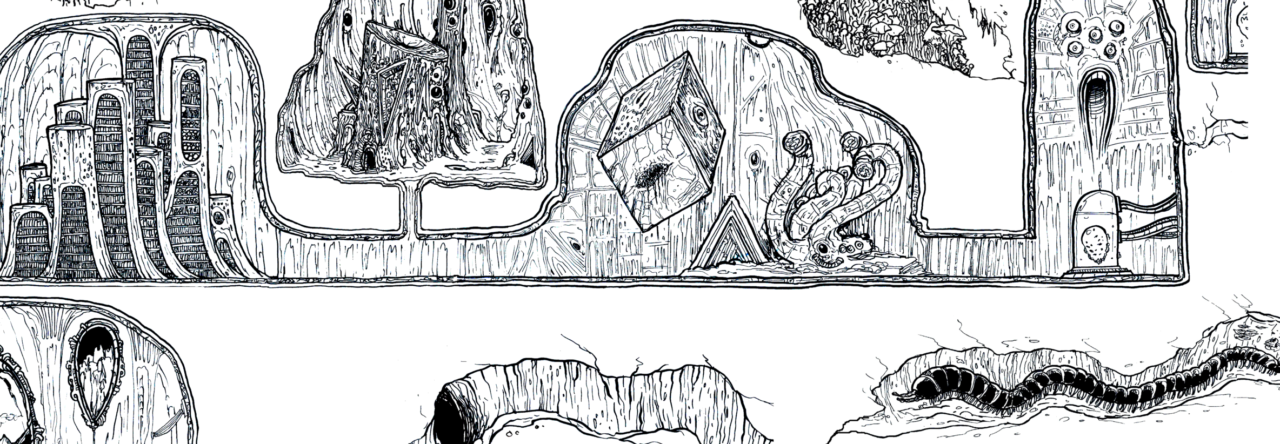

This is, in large part, why I wanted a physical, detailed map of the space, so that the players could see the city sprawling before them. It’s a common dictum that this is the wrong way to run cities, the idea being that maps constrain the imagination and pin down what could be a fantastic space too much. In drawing the map, I tried to create a visually appealing and chaotic space that enhances rather than undermines a sense of mystery. Yes, we can all see the Tower of Whispers on the map, but what could be inside such a bizarre spire in the middle of the city? Why is there a giant crater in the middle of the southern half and why haven’t people rebuilt over it? Is that a gigantic dragon statue broken into peices in the lower left-hand corner? And what is with the giant trees? I want players to look at the map and feel excited to explore. And, of course, there’s a hidden space as well – the Old City below, the massive sprawl of tunnels, sewers, caves, and ruins that the PCs have only partially explored.

The aesthetic I’m going for, then, is explicitly a maximalist one – in some ways, “the Baroque” is a good descriptor for what I’m attempting.

Historically, the Baroque was aligned with a Catholic counterrevolution against Protestant austerity and simplicity; Baroque aesthetics strove to evoke a sense of awe and extravagence, with plentiful, ornate detail, complexity, sensuousness, emotion, and drama, in contrast to the dour severity that often characterized the Reformation. My goal in DMing is to create something of this vertiginous rush of complexity and detail, while still making the experience intelligible and player-driven. Indeed, player agency here is absolutely key: it’s vital that the players feel they can explore wherever they wish and find something engaging to interact with. Otherwise, the setting would end up feeling like a very pretty but ultimately flat series of backdrops that the PCs roll by on their way to and from pre-scripted plot points. To ensure this doesn’t happen, it’s important to distinguish between prepping and planning. The former is about providing a detailed, thought-through environment for players to explore and inhabit; the latter is about aiming for a specific narrative arc or set of story beats. I do a ton of the former and almost none of the latter.

During play, I keep the Hex map itself spread out in front of players at all times, so they can see where they are and how locations relate to one another spatially. I don’t always go street-by-street in describing everything as they move around the city – this would make the game very slow – but I do “zoom in” to a district level, street-by-street, once the party arrives in a given neighbourhood. I think of it a bit like how Planescape: Torment (a huge influence) handles city movement: there’s a map with districts, you click on one, and then you “zoom in” to that particular district’s individual streets.

If the party decides to “zoom in” on a specific location, I always have something ready – I’m not suddenly grasping for details that aren’t present, and forced to make something up or generate something randomly that wouldn’t be as interesting as something I thought up ahead of time. I’ll have descriptions of each street, NPCs worked out, encounter tables when appropriate, and often some oddity or other the party could choose to interact with, like a weird homunculus wandering about outside a condemned building or a vagrant spellcaster painting magical murals on a wall.

Consequently, I rely on what I think qualifies as extremely heavy preparation – again, prepping, not planning. What I’m aiming for here is what Joseph Manola over at Against the Wicked City identifies as the essential quality for good roleplaying books: “the contents need to be something better than you could come up with, unaided, simply by following cliches and/or random madlibbing and/or coming up with irrelevant filler.” Whenever I write something down, it needs to be better than something I could come up with on the spot at the table, better than a cliche, and not irrelevant filler. There is no Powered by the Apocaylpse-style collaborative setting-building here: the PCs do have backstories and I do incorporate those into the texture of the world, but I don’t ask them for details about a scene or give them opportunities to shape the world outside of the actions of their characters. Those actions are consequential, sometimes massively so, but they are bound by an in-universe logic and constraints. Similarly, I don’t rely on random die-rolls or other procedural heuristics or techniques to generate street-maps, encounters, or NPCs. It must all get planned exhaustively, so that when the players stray from the beaten track the spaces feel lived-in and authentic and just as interesting as the parts I expected them to visit. This means drawing a crazy-detailed city map with every street and major landmark indicated, and producing extensive notes for every likely adventure location – I’m currently sitting at about 270,000 words for a total of 38 sessions so far (yes, I’m behind on recaps).

Obviously this means a lot of writing and drawing. But, as the DM, this is to me a huge part of the fun: I don’t think of writing adventure notes or drawing maps as work. I have other hobbies and leisure activities and things to do, of course, and a job that takes up a lot of my time, and I do occasionally take hiatuses when things get too busy to keep up with the campaign, but I find the act of creation and then sharing that creation with a group of people incredibly rewarding – so this preparation really isn’t a chore. All that said, I do use certain procedures to make this easier on myself.

Pre- and post-play Procedures

I organize the campaign using groups.io, a wonderful email group service with a lightweight, easy-to-use interface and the ability to quickly and painlessly distribute polls to those within a group. Before every session, I post two polls: the first is a scheduling poll to see who can play when, and the second is a poll of broadly defined adventure possibilities, usually picking up on things the characters did in the previous session, or sometimes reflecting events that have transpired in the setting. Some of these are ongoing, so if the party neglects them, they’ll change: for example, the endless winter caused by the Harrowgast in some of last year’s sessions was something the players ignored in the polls, until rioting in the streets and famine made them take notice. Genial Jack’s nightmares are another example – the players heard rumours that Jack’s sleep was disturbed, but it took them a couple of sessions to look into it, and if they hadn’t, things would have gotten worse and worse.

The polls function a bit like a quest log or journal in a computer roleplaying game, but many of the available threads are generated by the actions of the players, rather than simply representing “available jobs” (though there are some of these too). In a recent session, for example (one not yet posted to the blog), we picked up on the backstory of Caulis the homunculus, whose dead creator had saddled the character with a demonic debt – something the player had included in their back-story since character creation. In another, Comet’s player had mentioned the waspkin was hanging about in the Feypark to avoid harassment by the Crowsbeak Thieves’ Guild, and was getting to know the plants and animals there; this led directly to a fun little adventure where the character shrunk down to rodent-size for some Redwall-style medieval animal hijinx. In the two-part Château de la Marche adventure the party explored a character’s familial estate and faced off against a villain they’d failed to kill in an earlier adventure. In our most recent session, Yam’s player had a clever idea for keeping the reality-warping Book of Chaos safe, and so I wrote an adventure planned around the idea. The idea here is to avoid making the characters passive, but to view them as active agents in a world that reacts to them; the poll, which players themselves can comment on or add to, simply lets me see which direction they’re headed.

Polls indicating a rough plan for future sessions let me prepare adventures and areas for exploration more extensively. In this case, a detail I’d improvised in the previous session led to option 6, which tied for the most popular option. In discussion below, we decided to go for option 6 over option 1…

Of course, once we arrive at the table, the party is free to go anywhere. But having a broad direction discussed and decided ahead of time not only lets me prep the areas we’re going to play in more extensively, it keeps a big group of players on track and avoids having to recap every single thread of the unfolding game every time we sit down to play. There’s no railroad, and no pre-scripted story, and no invisible walls that keep players stuck in a single area, but there is a consensus going into each session of what the party would like to accomplish. It also means that players who can only come every few sessions – or even those who stop by once or twice a year! – can jump into a session easily without being paralyzed with too many choices.

After each session, we use an extensive Google spreadsheet to track experience, which also shows how much XP each character needs to level. This, along with the session recaps I post here (massively facilitated by the notes my players take), helps a big group to maintain a sense of cohesion. Those who’ve missed sessions can read the recaps to catch up on what they’ve missed and make sure character sheets are up to date.

Adventure Hooks

While it’s always up to the players where they want to go and what they want to do, and I try to plan sessions in reaction to what the players have done previously, I do have some stand-bys for common adventure hooks. These include:

- Adventures related to a PC’s faction. Most of the PCs are members of an arcane university (there are eight: Fiend’s College, Umbral University, the Académie Macabre, the Citadel of the Perptual Storm, the Institute of Omens, the Warders’ Lyceum, the Metamorphic Scholarium, and Master Melchior’s School of Thaumaturgy & Enchantment), a thieves’ guild (the big ones are the Crowsbeak and Ravenswing guilds), religious organizations (the chief gods of Hex being the Archdemons, the Unspeakable Ones, the Mother of Spiders, the Magistra, the Charnel Goddess, the Elder Trees, and the Antinomian), and other factions, like the Faerie courts or wizardly cabals.

- Adventures related to a PC’s backstory. Most of my players wrote brief backstories with little adventure seeds scattered throughout them, providing plenty of opportunities for adventures.

- The “main quest” items they’ve been hired to recover all have adventures associated with them.

- Calamities and other events invite PC participation. The endless winter, Jack’s nightmares, looming war.

Running the Game

During an actual session, I more or less proceed as follows:

- Players arrive. Drinks are poured, food is ordered, socializing commences until everyone is present.

- The game starts. I start a playlist I’ve prepped beforehand on my Google Home, usually consisting of various ambient/videogame soundtracks.

- I go around the table and ask each player what their character has been doing between sessions. Because we play a very episodic game, it is relatively unusual for the group to pause “mid-adventure.” Each player takes 3-5 minutes to respond, so this usually takes beteen 15 minutes and half an hour. For example, Armand’s player has a series of strange botanical/alchemical experiments the character is undertaking.

- We segue into what I think of as the “preparation phase” of the game. At this point I will remind the players gently about the objective they voted on before the session. Then I step back and let them play out a quick scene, usually in a tavern or in one of the houses of the characters, as they plan whatever venture they’re undertaking, be it a dungeon crawl, a heist, a political meeting, a wilderness journey, an auction, a trip into the nightmare-haunted mind of a gigantic primeval whale, etc. This usually takes a few minutes, sometimes longer if there is substantial disagreement among the party members about how to proceed.

- After the preparation phase is complete, we launch into the “main phase” of the game – however the players want to tackle it. Generally this wraps up by the session’s end, but new adventure seeds will be uncovered, ideas had, conspiracies unmasked, etc. Sometimes the party needs to pause midway through, but this is rare. I’ve become fairly adept at judging how long it takes for a given adventure to be completed. During this phase, I periodically try to check in with everyone – with a big group, its easy to sink into silence and let others take the lead.

- The session concludes, and we often briefly discuss what we might do next.

- I use groups.io to notify players of XP, update the spreadsheet, and post polls for the next session time and objective. Players discuss any possibilities and hash out a rough plan of what to do next session, ask questions about gear, leveling, etc.

Further Notes

There’s a partially justified objection, both in some OSR circles and in indie/narrativist/story-game circles, of a very prep-heavy style of play, and most versions go something like this: if you prep too much you get precious about your setting and/or your story and will inevitably railroad players, and prep-heavy DMs are usually “frustrated novelist” types who really wish they were authors telling their own story rather than referees of a game. There’s real wisdom here – this is why people dislike Pathfinder adventure paths and bloated AD&D adventures and all that kind of thing.

However, again, heavy prep does not necessarily entail pre-scripting or planning a plot. Indeed, by extensively preparing locations and NPCs, I find myself feeling reassured at the table. I am also never gripped by panic of a blank space on the map – if the players decide to go somewhere I hadn’t envisioned, odds are I have at least some notes for what’s there, and enough modular material (encounters, adventure seeds, weird happenings) that I can make the area feel interesting enough that it doesn’t become obvious when the players are leaving the rough path I envisioned for them.

None of this makes good improvisational skills superfluous. I make things up all the time, improvise almost all NPC dialogue, and of course embellish my notes with invented details. Inevitably, the players will do things I don’t expect and come up with plans and ideas I never would have imagined. Having a wealth of setting information on hand lets me roll with the punches. Prepping locations and NPCs rather than plots means that there’s no “script” to deviate from and thus no “wrong” way for the players to proceed.

There’s also a long list of things that I gloss over or just plain don’t care about when I’m actively DMing a session:

- Precise timekeeping. If the players ask, I tell them a time, and when it’s relevant to the adventure, I keep a loose sense of what time it is in a session, but otherwise I just don’t care.

- Precise book-keeping. If we were playing a gritty wilderness survival game or a pure horror game I’d care much more about this, but since the party is in a rich metropolis, I always assume they are well fed and have access to supplies. They still need to buy specific equipment, and sometimes we will roleplay shopping, but a lot of this gets done between sessions. If someone forgot to buy arrows for their bow and would really like to be able to shoot things, whatever, we’ll retcon that they bought them. With a group of 6-7 players per session, it just doesn’t make sense to spend time roleplaying merchant encounters excessively or fussing over exactly how many days of rations they have left.

- Rules discussions and minutiae. I and my players are very much “rulings not rules” people. They trust me to make fair decisions. Combat in the game is common but not the main activity most of the time, and I play fast and loose with 5th edition’s fairly flexible rules system, interpreting PC intentions and actions generously, and making quick calls when needed. I can’t remember the last time there was a rules dispute at the table, but if someone discovers a rule that got ignored which might have benefited them or something, I’ll give out Inspiration as recompense.

- Balance. I regularly give the players access to magic items that are pretty powerful tools for characters who are at this point mostly 4th-6th level (like the Head of Granny Midnight, the Portal Chalk, or the Rod of Mind-Swap). I also regularly throw monsters at them that are way above their recommended CR. They’ve played enough with me to know when to run and how to play intelligently without getting killed. This is a pretty standard principle of sandbox play generally, but it’s one I try to lean into.

So, there you have it – the procedures and philosophy underpinning my Hex campaign. Let me know if there’s anything you’re curious about – I’d be happy to answer any questions. I plan on writing more posts like this in the future fleshing out additional details both of how I DM and how I design dungeons, cities, and adventures.

Andrew Sutton

Very interesting article. I’m currently putting together a Wilderlands campaign and although I want to base it around a town (Tell Qa) rather than one of the larger cities such as CSIO or CSWE I found it encouraging to find someone else preparing the urban area in detail but with no desire to rail road characters. I’ve added your blog to my RSS feed app so will keep a lookout for more articles. Keep up the good work!

Bearded-Devil

I’m very glad you enjoyed it! The Judges Guild approach to this sort of thing is close to my own. It’s interesting that that style is in many ways very legitimately “old school” – City State and Wilderlands come out in the 70s – but has been in many respects overlooked (or even repudiated) by some in the OSR more taken with procedural generation. It seems to me that the totally valid praise of terse/efficient prose and the rejection of things like boxed text or pre-scripted stories has sometimes been intertwined or equated with a zeal for minimalism in adventure design generally, and I chafe against that instinct.

Shahar Halevy

I’m in awe of this – I support the sentiment that any pre-written material needs to be something I couldn’t come up with myself, and honestly your plots, maps and amount of detail really resonate with me. I honestly could take some of your work as a basis to make something of my own very easily. If your campaign notes and maps were available I’d buy them in a heartbeat.

Thing is, I lack some key things to really push my campaigns to reach this amount of detail, namely prep time (but also drawing skills and good note-taking habits). All of your ideas are things I could see myself coming up with individually, but more sparingly and after hours of contemplation and conversation. This is why I thirst for stuff like this to jolt my imagination. Great work, really. I envy and applaud you.

Bearded-Devil

Thanks for the kind words! I do have plans to release versions of my notes (and there is a plan to release the map and some other material, just been a few delays). The goal would eventually be to publish something with street-by-street descriptions of everything in Hex, with significant shops, taverns, guildhouses, and other structures detailed, plus all important NPCs and factions, some monsters and spells, and other content, including a handful of tables for random encounters and quick NPCs.

Ideally, at the table the players could say something like “we go to Raven Court,” the DM glances at the book, and they know at a glance that the court contains a candle-shop with candles made from human tallow and specialized candles made from the fat of executed criminals, for example. Or they take a shortcut through an alleyway in a rough part of town, the DM rolls on an encounter table, and instead of “1d4 thugs” or “1d6 dire rats” they get something like “A will o’ the wisp, as might have been seen in the ancient swamps that once sprawled here before they were drained, leads foolish adventurers to a particularly massive puddleweird hungry for mage-blood” or “A fractured mirror leans against one dingy wall of a nearby building. Anyone peering into it catches a glimpse of one possible death in their own future.” Or the DM needs a quick NPC and instead of rolling on a table to figure out that the random citizen is (roll) John the (roll) crossbow-maker who is (roll) a gnome who has (roll) bad breath, they can meet Jenny Greenbeast, a Crowsbeak thief cursed by a magistrate for her crimes with the Curse of Terrible Volume (every breath, word, stomach-grumble, or sneeze she issues is deafeningly, astoundingly loud), or Patience and Languor Weevilbane, conjoined twins in the Ravenswing Thieves’ Guild renowned for their good looks and expertise in picking locks, or Persephone Lilac, an adventurer of some renown, dungeon-pale and strangely scarred, is unstuck from time, skipping across its surface like a peddle across a lake. So there will be some random tables, but even these aren’t “procedural,” they’ll just be enough of them to make the lists basically inexhaustible. That’s the plan anyway!

Shahar Halevy

Bloody hell this sounds amazing.

You have my utter support. It brings me great joy to hear you are working towards releasing your material – I hereby swear I’ll DM it as soon as it’s available.

Sean

This is very inspiring. Thanks for taking the time to post it!

You mention that you run about 10 players, but not all show at the same session. How many players do you typically have at the table in a given gaming session? I am guessing 5-6, based on your “What has your character been up to?” between sessions, point.

squeen

A very nice write up. This is very similar to the way I run the home campaign—preparing the world a few days before the players head in any particular direction. Improve is nice, but we I try to write something down with the luxury of a little bit more time than the split-second it comes up during the game, a lot more detail flows into the world.

The whole procedurally generate school of thought leaves me a bit underwhelmed.

Now, if only I had your talent for drawing maps and building!

novum

An excellent read; I felt myself wishing I was playing in this game as I read. The maps are very eye catching and really pull one into the world, as do the names (or at least the ones I see on the maps).

Besides aesthetic quality, I’ve always felt names are so important to how much one is willing to buy into the fantasy world and these just brought the sounds and smells of these locations to the senses….

Ancalagon_TB

I feel somewhat … validated in my methods. I too am a deep prep person, and I’m at my happiest when I feel I *know* my city, that I understand how it works so well that I can improvise anything in response to what my players do – how would the alchemist cabal react to this crazy PC scheme to turn trash into quicksilver?

I don’t have the level of minutae you have however, but I dive deep in other details. What’s the GDP of the Yellow City? How much gold does it take to bribe a Slugman House? I can tell you 🙂

Allan Prewett

Don’t forget the excellent City of Haven by Thieves Guild. A great and extensively detailed city that unfortunately was never finished.

https://www.diffworlds.com/

Look in the tab Gamelords

HDA

This is great. I have always avoided city adventures like the plague, but now I’m trying to run the CSWE for my home group and your whole Hex game is a great inspiration! I have been struggling with balancing the procedural method of books like Vornheim, or something more detailed like this. Lord have mercy I wish I could draw!

Bearded-Devil

Thanks! A lot can be done with mapping tools like Inkarnate and whatnot. I’m sure it’s very possible to balance a CSWE/Hex and procedural approach, maybe by having a detailed map of districts with individual characteristics and points of interestm, and using the procedural stuff for actual street generation.

Josh

Incredible stuff. I agree with you 100% about prep, and wanting unexpected corners turned to feel “real.” That’s how I run my games, too.

Bearded-Devil

It seems like a very minority opinion these days – low-prep/procedural play gets applauded a lot, and world-building is sometimes framed as self-indulgent or even pointless. Glad the post resonated!

Bradley P

Just finding this, great piece!! I’m preparing a Shadowrun citycrawl game and a lot of this framework might really work for it. Nailing that sense of exploration where the players decide to go to a new location and you have something prepared to describe what they encounter and set them up for interesting new possibilities is exactly what I’m going for. Nice work, and thank you!