Having finished A Machine for Pigs I can now give it a more thorough review. It’s certainly a worthy successor to The Dark Descent in most respects, and surpasses it in some. There will be a few mild spoilers below, so read at your own risk.

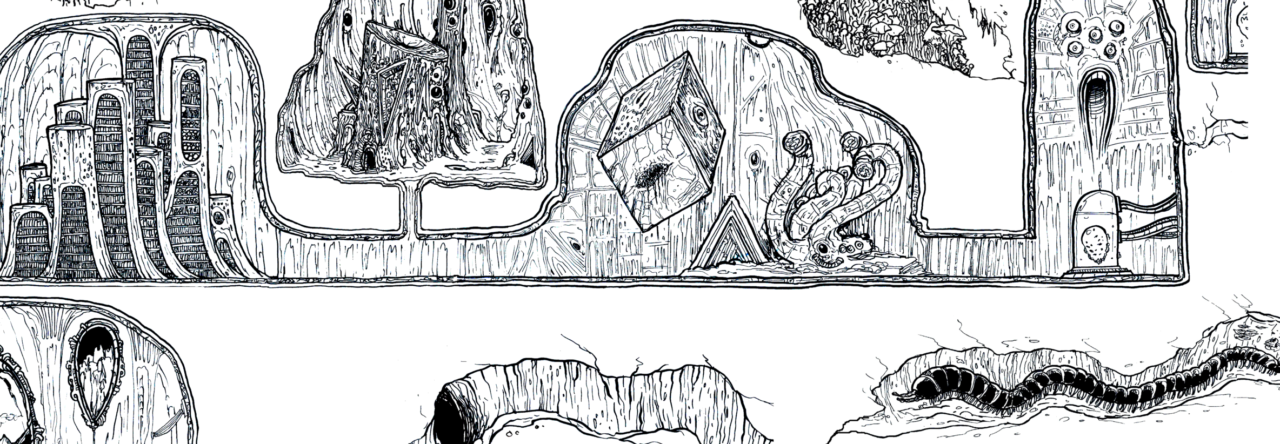

As with its predecessor, A Machine for Pigs is brilliantly atmospheric, using a combination of sounds, shadows, music, and text to great effect. The prose in the game – of which there is a great deal – is magnificently written: gruesome, rambling, poetic, and thematically profound, replete with motifs of animality, excretion, mechanization, sacrifice, spoiled innocence, and contamination. The levels are beautifully designed, a disturbing series of pens, abattoirs, seeping sewer tunnels, conveyer belts, generators, and churning gears. The industrial bowels of the Factory juxtapose cramped, claustrophobic tunnels with spaces of cavernous enormity crossed by rusty, zigzagging catwalks, alternating between submarine-like closeness and dizzying vastness. The dust and cobwebs of Brennenburg have been replaced with oil and excrement, the crumbling stone with hissing pipes and buzzing electric dynamos. The gameplay in A Machine for Pigs is stripped down to the point of simplicity, but what it does give us is genius. The electric lantern replacing the oil lamp of The Dark Descent has an interesting feature: it flickers rapidly whenever a monster is near (other electric lights behave the same way). Once I realized why the lantern was periodically flickering, I became conditioned to react to it in a certain way: whenever I caught it flickering I’d immediately turn it off, crouch down, and seek a hiding spot. The lantern not only creates a unique and original gameplay element, it has the added side-effect of reducing the player to the same level as an animal responding to a Pavlovian stimulus. By the game’s end, every time I saw the lantern flicker I would experience a set of physical and mental reactions – the game had literally rewired my brain to its own ends, making me its experimental subject, its lab animal, setting up obvious resonances with the porcine monstrosities that haunt the Factory’s tenebrous corridors.

As a protagonist, Oswald Mandus is a disturbing and fairly original character. Though I wish A Machine for Pigs had kept up the habit of reading journal entries in voiceover, which I liked in the first game, the phonographs scattered around the Factory along with the telephone conversations and flashbacks throughout the game give us enough of Oswald’ voice to get a proper feel for him. His motivations are more complex and unsettling than Daniel’s, and while the protagonist of The Dark Descent always felt like an outsider, an intruder exploring an alien environment, Oswald’s Machine is an uncanny space, familiar and yet unfamiliar – both because Oswald built the Machine and because the environment is riddled with clues that he’s been through the labyrinth very recently and is now retracing his footsteps. The character’s intense mysophobia makes me feel like there was a missed opportunity for some kind of “contamination mechanic” to complement the first game’s sanity mechanic. Steam-shower decontamination rooms punctuate the fetid, mechanical entrails of the Factory, but without any reason to enter them beyond getting to the next area they’re just another set of switches to fiddle with, and by the third or fourth time we enter and exit one they’re rather old hat. But if there’d been a real gameplay-based reason to use them – say, Oswald freaking out if he became too contaminated, maybe coughing and spluttering and so alerting potential enemies to his whereabouts, or even physically deteriorating after being exposed to Compound X, the quasi-alchemical serum crucial to Oswald’s creation – the anxiety around delving into canals awash with excrement or tunnels swirling with mephitic vapours would have been much enhanced, and the decontamination rooms would have provided a sense of relief. Even without such a mechanic, however, we still get a strong sense of Oswald’s distaste for the unclean, his complicated loathing and pity for a world he considers utterly disgusting, a desacralized reality whose existential horror drives Oswald to build his abominable edifice. At first I assumed the Machine must have been created as a means of extracting profit, the ultimate embodiment of Victorian capitalism and imperialism, but its purpose turns out to be far more deranged, and Oswald’s complex motivations, obsessions, and neuroses are tied into and physicalized by the Machine itself.

The monsters are very well-designed, and suitably grotesque. Interestingly, by the end of the game they elicit as much pity as they do fear or hatred. The “Manpigs” embody a whole host of contradictions: they are brutal and violent yet also strangely innocent, even child-like. The game invites us to read the pigs as degraded proletarians but also identifies them with Mandus’ children, his creations; they are, ultimately, his victims. They symbolically represent an array of human lusts and appetites, the animal within us – our tendencies to sloth and gluttony, our bestial urges. At the same time the game encourages us to feel responsible for them: they horrify not only because they’re stitched up, misshapen beast-people but because Mandus made them that way. In keeping with the transition from the sublime, quasi-religious terror of The Dark Descent to the revulsion and disgust common in the urban Gothic, the Manpigs are more scientific than mystical. The true horror in A Machine for Pigs is derived not from the monsters but from their creator, and from the inexorable encroachment of modernity itself. The reduction of humans to meat and of the world into a machine “fit only for the slaughtering of pigs” conjures images of Auschwitz and the trenches of the Somme, connections which the game eventually makes explicit. The Manpigs are thus perfect examples of the urban Gothic’s strategy of monster-making, allegorizing a host of social ills while simultaneously problematizing categories (human/animal, innocent/evil, natural/artificial, organic/machine), disturbing our assumptions and holding up a fractured mirror for us to gaze upon. Rather unusually for a game so interested in bodies and body-horror, the monsters here aren’t especially sexual in any way; perhaps the developers felt that Justine, with its monstrously sexualized Suitors (and the vaguely venereal wounds of the Gatherers in The Dark Descent) had covered that ground sufficiently.

The game is not without its blemishes. While its atmosphere is superb, it pulls its punches a bit too often – the monsters aren’t common enough to be as oppressive as they could be, and sometimes their deployment is a bit sloppy. The game could also show a bit more violence; at one point the Manpigs rampage through London’s streets, but we don’t see enough evidence of their bestial destruction to make it sting (in general, the London-streets levels are amongst the weakest in the game). The lack of an inventory has its upsides, but it limits the creators’ ability to craft compelling puzzles, and they don’t manage to compensate: the “puzzles” are incredibly easy, easier even than most of the original Amnesia’s. I feel this is a direct result of the Chinese Room’s design style; there’s just not much to do besides explore the game’s admittedly gorgeous spaces, occasionally dodging a monster, flicking a switch, or installing a new battery. As much the tinderbox-collection and lamp-oil rationing in The Dark Descent was a mixed bag, it gave you something to look for as you explored Brennenburg. A Machine for Pigs could have provided other reasons to explore every corner of every level, like difficult puzzles that require moving back and forth between areas (some timed puzzles would have been welcome). In the same vein, the game is far too linear, which is disappointing considering how open and sprawling Dear Esther is. In The Dark Descent the castle had hubs, central spaces from which other levels branched: the Entrance Hall, the Back Hall, the Cistern Entrance, and the Nave. You made choices about which area to go through, and sometimes had to return to areas you’d previously explored, occasionally facing new threats along the way, like when the Shadow infests the Nave with its oozing horror, collapsing whole corridors and snuffing all the lights. In contrast, A Machine for Pigs is fairly linear. The Mansion at the beginning is nicely sprawling, and the Factory Tunnels have multiple choices, but for most of the game your movements are very limited. Towards the end you are literally on a conveyer belt, which has nice thematic connotations but does bring home how straightforward the game ultimately is.

The two Amnesia games can teach us a great deal about game design, I think, particularly when it comes to horror. First and foremost, they demonstrate the vital importance of atmosphere. Monsters are scary in large part because of the contexts into which they are placed. Unlike, say, Dead Space, where the necromorphs show up almost immediately and never go away, both Amnesia games know the importance of revealing things very gradually: horror in both games is a kind of strip-tease, and the agonizing build-up to the full reveal is absolutely central to the total effect. Both games also illustrate the value of empty space. Empty rooms, corridors, and other areas, when presented atmospherically, are more than padding: they pace an experience and make the player(s) wonder about whether something will be found behind the next door or round the next corner. If a dungeon is stocked to the brim with monsters, there’s really not much opportunity for suspense. A Machine for Pigs also demonstrates the utility of repetition to ingrain certain behavioural patterns into players: while care must be taken for encounters not to become stale, the repetition of certain signs and images, like the flickering of the electric lantern, can be used to evoke powerful reactions. Such motifs not only provide a through-line to an adventure, they can be used to elicit dread and anticipation. Say, for example, a particular monster exudes a signature stench, and great emphasis is placed on the particular quality of its odour; then, whenever that odour is present, the players will tense up in anticipation. Finally, both games can be seen as templates for the deployment of Gothic tropes in a gaming context, a series of stock images and situations to be drawn on and borrowed from.

Up next on my list to play: Outlast. Having just written a scenario set in an asylum I’m curious to see a different approach.

Leave a Reply