I recently bought Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, sequel to the brilliantly macabre survival horror game Amnesia: The Dark Descent. The first Amnesia remains one of the scariest games I’ve ever played, and the best adaptation into game form one could hope for of a classic Gothic novel of the late-eighteenth or early-nineteenth centuries, with a generous bit of H.P. Lovecraft thrown in for good measure. I have replayed Amnesia several times now – the game is short in theory, but often takes a long time in practice, because of the paralysis of terror that fills you while you play it – and it has had a very strong influence on my tabletop games and other writing (even, possibly, on my scholarship). It remains one of my favorite games of all time, up there with Thief: The Dark Project and Half-Life 2. I’ll post a full review of A Machine for Pigs once I’ve completed it, but here a few of my first impressions. Needless to say, there may be some gentle spoilers below.

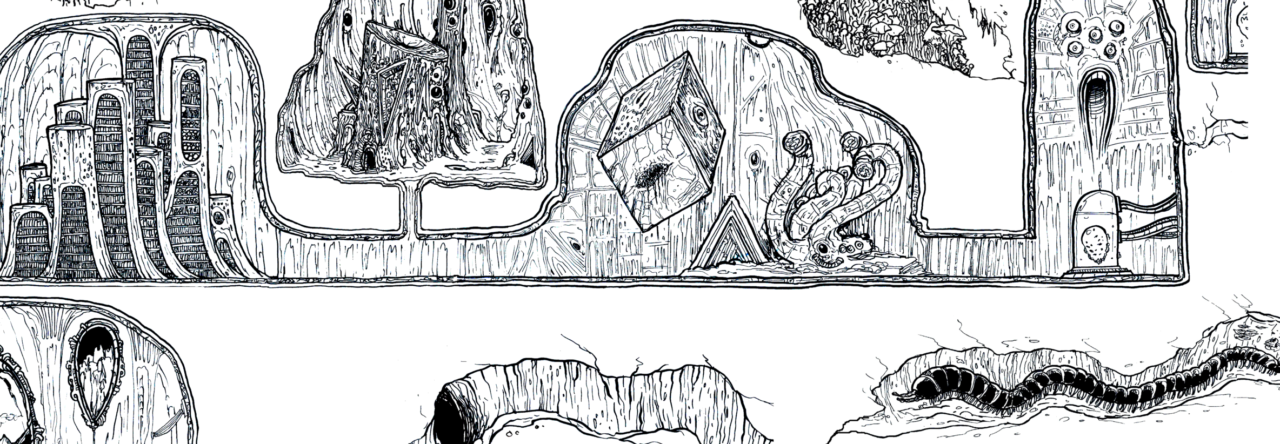

Some background on the game may be useful: while the first game was developed entirely by the Swedish indie company Frictional Games (also responsible for the Penumbra series), the second was developed by The Chinese Room, a studio best known for their unconventional exploration game Dear Esther. The game takes place about a hundred years after the original, in Victorian London rather than rural Germany. Already with the choice of setting the game distinguishes itself from its predecessor. The Dark Descent was a game centered round the idea of an ancient, terrible, and largely unknown force: “the Shadow,” a mysterious, Lovecraftian entity, summoned accidentally out of Egypt by the hapless protagonist, Daniel. The game fixated on tropes taken from the original Gothic of the eighteenth-century (I may have to write a proper academic article about this…): the aristocratic secondary villain Alexander, the crumbling, black castle, the hidden tunnels, the remote location, the emphasis on the unseen and the unknown, on what Ann Radcliffe would call terror rather than horror. The Dark Descent is a game of the “terrorist” school. The game punished you for even looking at the monsters in The Dark Descent: when a monster appeared you caught a glimpse of it and then ran, because otherwise you were dead (you have no weapons, and two or three hits kill you), and looking at a monster drained your sanity. You had to painstakingly scavenge and ration your tinderboxes and lamp oil: your most valuable resource was light, allowing you to navigate the tenebrous labyrinths the game delighted in (especially the Storage and Prison levels, which could be real mazes). On the other hand, light was dangerous, because it could alert monsters to your presence. There was certainly gore in The Dark Descent but it was used very sparingly, and often there was more a suggestion of violence than actual bloodshed – torture rooms where old implements slowly rusted, or half-remembered flash-backs of people screaming. Sound was vital to the game’s strategy of fear, but The Dark Descent really didn’t go in for the jump-scare much: it was more interested in slow-burning paranoia. Instead of being startled you’d end up crouched in a corner, your character’s sanity draining in the darkness, willing yourself to open the rotten old door from behind which you think you heard a bestial groan. While in many ways A Machine for Pigs replicates aspects of this experience, it owes much more to the Gothic resurgence of the nineteenth-century fin de siècle – a predominantly urban Gothic more attuned to social disorders, science, and the boundaries of the human.

So, A Machine for Pigs. Firstly, the gameplay remains largely the same as Amnesia: The Dark Descent – first person, you have no weapons, you wander around a sprawling environment trying to find your way down deeper into the complex. There are some very key differences, however. Most prominently, A Machine for Pigs does away with the inventory entirely. You have no sanity score, and your health is invisible (in the previous game, these were displayed in your inventory, symbolically represented as a heart and brain); you can still pick up items, of course, but you can only move one at a time, you can’t stow them in pockets as capacious as a Bag of Holding. On the one hand, losing the inventory annoyed me, because one of the thrills of The Dark Descent was the intense relief at having found an object you needed for one of the game’s puzzles, and the rationing of your tinderboxes, lamp oil, and laudanum added a resource-management element that contributed to the overall anxiety of exploring Brennenburg. However, there is an upside. Constantly in The Dark Descent I found myself looking for opportunities for respite from the harrowing experience of actually playing the game – not just lingering in areas that felt safe, but obsessively going through my inventory items, examining them, trying to combine them. The inventory screen took me out of the world for a moment, relieving the tension. Without the inventory screen in A Machine for Pigs there is less opportunity for such relief, forcing me to spend more time in the game-world itself. The lack of sanity score is interesting: your sanity no longer drains in the darkness (a consequence of the original protagonist’s nyctophobia), so there’s less of a compulsion to use the lantern, which is now electric. As a result, I use my lantern less, but when I do I find myself using it purely for light rather than to keep my sanity from draining. While I miss the anxiety that dwindling resources provoked, in a sense I’m actually more immersed with the electric lantern, because there’s no dissociation: while in the past I was using light not only to see, or to combat my own fear of what lies in the darkness, I was using it to make sure a statistic didn’t drop. Sure, that statistic had consequences in the game (woozy vision and minor hallucinations and all that), which also added a lot, but there was still a degree to which my immersion was slightly undermined.

In terms of its capacity for fright, the game has not disappointed so far. Having played the first game, I fully expected the first segments of the game to be devoid of monsters and so felt relatively safe as I explored the first levels – a Victorian manor house, in significantly better repair than the mouldering fastness of Brennenburg – but as I got further and further into the game my anxiety started to ramp up, unsure of when the first real danger would appear. Even despite my knowledge that I was unlikely to encounter anything in the first half hour or so of play, the game still managed to unnerve me significantly. The Shadow periodically shook Brennenburg, dislodging stones and knocking over rotten beams; in A Machine for Pigs the same role is played by the eponymous machine (whatever it is), the “Factory” as the journals and phonographs describe it, a behemothic construct of gears and piping which I’ve only caught hints of so far, having just now descended into a series of tunnels below an old chapel or church attached to the manor. This, in itself, is fascinating. Numerous texts in the game indicate that Oswald Mandus, your protagonist this time around, has a deep disdain for God, referring to him as a hog, swine, etc – a position probably connected to the heavily implied death of Mandus’ wife. At the same time, man and machines are complexly deified and degraded in the journal entries and recordings. On the one hand humanity’s capacity for creation and vision is exalted, but on the other hand humans are consistently referred to in animalistic terms (most commonly, of course, as pigs); machines are likewise spoken of in rapturous terms, yet Oswald spits on Babbage’s vision of a thinking machine. While in the first game much of the terror revolved around ancient, unknown, and alien powers, like the Shadow, in this game the evil is man-made, modern, and disturbingly human. There are hints that Mandus brought something back from a fateful trip to Mexico – references to and models of ziggurats, ubiquitous Mesoamerican pig-masks, the suggestion that Mandus fell ill after returning from Central America – but the fiendish machine, and the Moreau-esque monsters which, at this, point, I have only caught the barest glimpses of, are (I think) Mandus’ creations, not some outside force’s (the Gatherers in The Dark Descent were created by Alexander, of course, but Alexander is almost certainly not human, but a supernatural being of some sort: he wishes to return to the world he came from). The focus on humanity itself and our creations rather than on horrific outside forces is far more in accord with late nineteenth-century Gothic works like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Island of Dr Moreau, and The Great God Pan – even when supernatural forces are involved in such stories they are usually tied to or released by human science, or at least human willpower.

As for the monsters themselves, as I said, I’ve only caught the barest glimpses so far, but from what little I’ve seen they’re going to be very unique. The monsters in The Dark Descent were mostly fairly slow: the Gatherers could get up to a decent clip when roused, but most of the time they were shambolic, lumbering zombie-like through the castle’s passages. Justine, The Dark Descent’s semi-sequel, went the same route with its Suitors – speedy enough when riled up, but usually slow and ponderous. The monsters in A Machine for Pigs, in contrast, seem much, much faster. They flit, quadruped, across passageways and catwalks, charging on all fours from place to place.

The game so far is also much more concerned with the domestic, a pleasingly Victorian transition. I liked Daniel in the first game but he was basically just an individual: there was no exploration of his family, and his back-story was explored only when directly relevant to the game’s plot. In contrast, Oswald’s back-story is far more detailed. We know the names of his wife and children, his social status, his profession (industrialist/philanthropist); we get a much better feel for Oswald’s personal obsessions and interests in this game. The game seems to be setting him as a mysophobe, someone intensely disgusted by and paranoid about filth and animality – fitting, considering his adoration of the clean, cold sterility of machines. His motivations are similarly more socialized and contextualized: while Daniel was basically on a quest for personal revenge (revenge for what Alexander had turned him into), Oswald is out to save his children, children I’m coming to think he may have badly abused in the past, given the unsettling cages (gilded, but still undeniably reminiscent of pig-pens) that he’s placed over their beds.

I’m looking forward to completing the game, though I’d estimate at this point I’m only about 10-20% through at most. When I’ve finished I’ll post a more thorough review, and perhaps talk about some of the things Amnesia can teach us about game design.

Leave a Reply