I’ve been reading and rereading a lot of William Hope Hodgson recently as part of my academic research, and after finishing his Weird short novel The House on the Borderland (1908) I decided to begin replaying a game that features another strange inter-dimensional house, Gremlin’s Realms of the Haunting, a wonderful old diamond-in-the-rough that, for me, possesses immense nostalgic value. Along with Heretic, Lands of Lore, Myst, and Diablo it holds a special place in my heart as one of the first computer games I played that didn’t involve shooting ducks or dying from dysentery somewhere in the American Midwest. I picked up the game a couple of years ago from gog.com on a whim, expecting to find it nothing more than a quaint trip down memory lane, but after playing it through once again I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the game’s incredibly rich story, complex mythology, eerie atmosphere, and engaging gameplay combine to create an experience that holds up shockingly well nearly two decades after its initial release in late 1996. The graphics, granted, show their age in a way that other adventure games from the same era (for example, the unfathomably gorgeous Riven or the stylish masterpiece Grim Fandango) avert; the pixelated 3D graphics, the lack of properly three-dimensional objects in the game, and the clunkiness of the Normality engine make for a game that now looks somewhat primitive and artificial, with a maximum resolution of 600×480. The cutscenes are entirely live-action, the actors largely acting against a green screen and delivering campy but surprisingly competent performances, and while generally I’m not a huge fan of the strange effect seeing live actors transplanted into a computer-generated setting produces (increasingly, in fact, I dislike cutscenes in general), here the FMV works rather well: actors David Tuomi and Emma Powell portray the protagonists – moody, trench-coat wearing Adam Randall and alluring psychic Rebecca Trevisard – quite ably, and their physical performances give both characters much more personality than the sprites or 3D models of the day would have. In an age of photo-realistic computer-generated cutscenes there’s something charming and quirky about the live-action performances, which are supplemented by a vast amount of voice work; every painting, suit of armour, door, weird sigil, candlestick, coat stand, and cartridge in the game can be examined, with Adam (and sometimes Rebecca) orally commenting on the object in question. The clips aren’t so frequent that they become annoying, but they’re common enough that spread throughout the game there’s over 90 minutes of FMV.

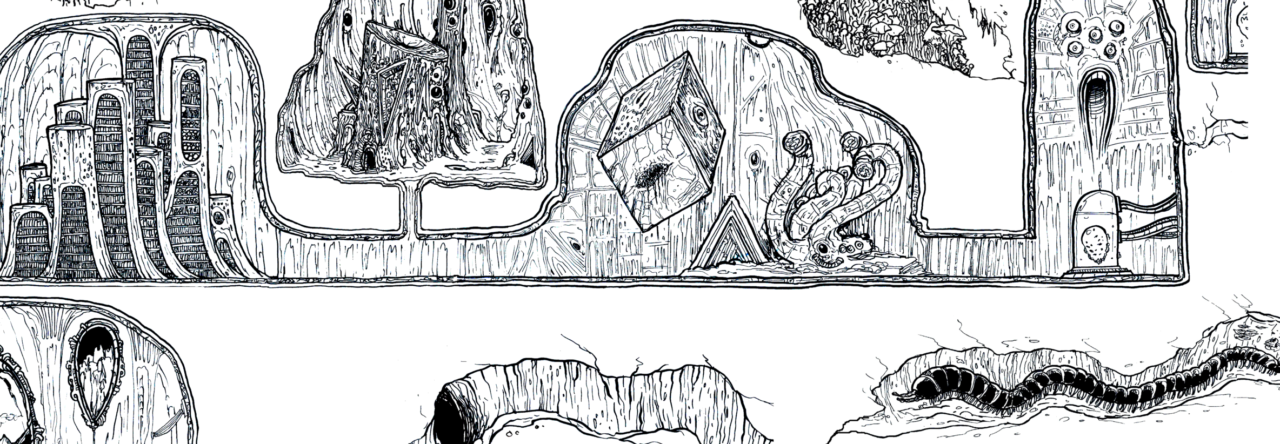

As a whole, in fact, Realms of the Haunting almost benefits from its technological limitations. Modern horror games and first person shooters tend to be relatively brief affairs, in part as a consequence of their graphical extravagance; even Half-Life 2, which I think of as quite a long game by today’s standards, clocks in at around fifteen hours on average and can certainly be completed in much less. In contrast, Realms of the Haunting lasts for well over forty hours, and little of it feels repetitive in the way that some long games can. The graphics may be crude but the levels are well designed, sprawling and intricate, filled with secret doors, sub-levels, portals, puzzles, mazes, Escheresque chambers, teleport pads, hidden nooks, and other curiosities. Atmospheric details abound – like a typewriter spewing creepy, repetitious text of its own accord, or the Satanic carvings in the depths of the Mausoleum – and the game manages to cultivate a fairly unnerving atmosphere at times. It never approaches the masterful terror elicited by the likes of Amnesia nor the frenetic, adrenaline-fuelled tension of something like Outlast or Bioshock, but it did occasionally startle me, and what it does manage very well is a dense aura of eldritch gloom and mystic strangeness. It’s tempting to throw around the adjective “Lovecraftian” here, but as the game’s writer and producer Paul Green notes, the game’s mythos is based primarily on real-world religions and occult systems, a syncretic Judeo-Christian mishmash with bits stolen from various Eastern religions, Kabbalah, Gnosticism, Spiritualism, Zoroastrianism, and Christian apocrypha. Green also cites John Carpenter and that amusingly lurid bit of messianic crackpottery The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail as influences, the latter of which is especially visible in the game’s depiction of a heretical secret society of corrupted Templars whose leader, the effetely nefarious Elias Camber (an anagram of “Bears Malice” and “Macabre Lies”), alias Claude Florentine, serves as one of the main antagonists.

The game’s slowly unfolding story (warning: mild spoilers to come) begins with what seems like a fairly hackneyed setup. Following his father’s death, Adam is tormented by dreams of a peculiar house in Cornwall which he eventually seeks out and enters; the decrepit old mansion, with its animate portraits, rusting suits of armour, mildew, and similarly Gothic accoutrements at first appears to be a staple haunted house of the most typical sort, but the scenario quickly become more complicated with the manifestation of Adam’s father’s ghost, a rather Shakespearean spirit that beseeches his son to free him from the agonies of Hell before being dragged back to the pit by a number of menacing armoured shades. Things only get odder as the game evolves and a complex tissue of associations between various angels, Goetic demons, elemental spirits, and mystic brotherhoods coalesces. Complicating the Manichean dichotomy of Light and Dark that dominates the central conflict are such enigmatic entities as the bizarre and grumpy gatekeeper-creature and Keeper of Time known as the Gnarl; the gibbering, phantasmal horror of the Ire with its hypnotic song and its bestial avatar, the Dodger (which, I suspect, may owe its inspiration to Machin Shin, the “black wind” that haunts the Ways in Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time, though I can’t be sure); a water deity, Tishtrya, ripped straight from Zoroastrian mythology; and the benevolent ghost of Aelf, a medieval knight and reincarnation of St. Michael – to name a few. Visions, weird magickal artefacts, relics, unholy brands, riddles, crypticisms, mouldering journals, and other miscellanea are scattered throughout, some of them providing clues as to the overall shape of events, others producing more questions than answers.

In fact, it takes quite some time (probably about 10 chapters or so) for a coherent picture of what the hell is going on to come into focus, and for much of the game you’re left physically and figuratively in the dark to a large extent, wandering the labyrinthine vastness of the old house and the tunnels beneath it, stumbling upon esoteric oddities and perils. This works immensely to the game’s advantage. Horror is a genre that really requires slow pacing; the best horror movies and stories know this, revealing their monstrosities only gradually, in an abominable striptease (as in, say, Alien). There’s an entire school of thought – exemplified in The Philosophy of Horror by aesthetician Noël Carroll – that claims that when we consume horror media we’re not actually craving fear or disgust, the chief affects the genre produces, in and of themselves; rather, we’re seeking compensatory pleasures for which these emotions are mere concomitants. The process of solving a mystery, of ratiocination and deduction and the play of proofs, imparts the actual pleasure, Carroll claims; everything else is a by-product. I don’t find Carroll’s theory especially convincing, but it can’t be entirely dismissed, either; I do think there’s something to be said for the appeal of the unknown and the curiosity it incites. Another, much older theory offered by weird fiction author and fin-de-siécle mystic Arthur Machen in his aesthetic treatise Hieroglyphics (1902) suggests that the best literature conjures a sense of “ecstasy,” by which Machen means the numinous, wondrous, and mysterious, and I think horror is uniquely capable in this regard, with its penchant for interstitial monstrosities and unknowable malevolences. Certainly Realms of the Haunting knows the value of a good mystery and in not revealing too much too quickly. In a certain sense, the game invites the player to become a bit of a mystic themselves, as you’re constantly compelled to seek a series of revelations, to uncover what has been hidden and, slowly, to piece together a picture of events from a confusion of disparate parts as your character participates in transformative rituals both sacred and profane.

Though the cosmic vistas Adam and Rebecca explore are intriguing, the house itself and its associated dungeons comprise the most compelling setting. Like the sinister Spencer Mansion of Resident Evil (released in the same year as Realms of the Haunting) or the ooze-infested ruin of Amnesia’s Brennenburg, the house is a sort of character in and of itself, sometimes seeming to possess a capricious will of its own. I have no idea if the eponymous house in Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland was actually an influence on the designers or not, but there are certainly some major similarities. Of course, the trope of the haunted house is a well-worn one, but what’s interesting about the house in Realms, as in Borderland and in the more recent postmodern take on the haunted house, House of Leaves, is the way the house functions not only as an example of the Freudian uncanny with its Gothic subversion of domesticity (not to mention its cavernous, quasi-uterine spaces) but as a locus of what China Miѐville would call the abcanny. If the uncanny or unheimlich is about the return of the repressed in a familiar-yet-not-familiar form – the manifestation of what Freud terms “womb-phantasies,” old wine in new bottles, and what Derrida calls the hauntological – then the abcanny is about a more radical unfamiliarity, an otherness and alterity utterly beyond our ken, always evading comprehension, resisting attempts to impose meaning or structuration. This sense of the cosmic, the weird, the awesome and the awful, the unknown (perhaps the ecstatic, in Machen’s terms) suffuses the house in Realms of the Haunting, with its faceless guardians and its interminably winding, unpredictable corridors, its doors which sometimes lead into dank cellars but which also open on primordial caverns and alien cosmoses and gigantic demon-summoning clocks. It’s this ambient numinousness erupting violently out of the quotidian architecture of Realms‘ house that makes it so special and surreal.

The gameplay itself is intriguing, as the whole thing is very much a hybrid of an adventure game, a Doom-style FPS, and a survival horror game; there are times when you’ll go for quite some time encountering only a few enemies, and others where you can’t go more than a room or two before activating some conjurer’s circle and summoning another fiend or three that require mowing down. At the beginning you have to husband your resources carefully, as the game provides little ammunition for the pistol and shotgun you quickly acquire, and the only other weapon you initially possess, a sword, is difficult to use without being carved to ribbons yourself by the mostly melee-focused foes. It doesn’t take too long, however, for rechargeable magic weapons to make an appearance, at which point I stopped using guns almost entirely and stopped worrying about searching every corner of every room for ammo. The controls are clumsy in a way that the game kind of pulls off (again, the technological limitations here actually help as much as hurt), as when you’re fumbling with the controls for your sword, shield, or pistol while some hooded Thing bears down on you there’s a nice little spasm of panic that a smoother, more intuitive combat system would have effaced. Large swathes of the game, however, are spent puzzle-solving, as in one strange sequence set in the Room of Riddles in one of the game’s four planes of existence (Realms), which seem loosely based on the four Kabbalistic layers of reality. The game as a whole is fairly linear, but individual levels are quite open, and once you’ve dispelled some of the mystic seals that keep certain doors in the central house shut you can explore the entire non-linear sprawl of the mansion, with the game often requiring you to retrace your steps and return to particular rooms or other areas. Dungeon-crawling fans will find much to enjoy in Realms’ maze-like passages, which are variegated enough not to get monotonous.

Realms of the Haunting absolutely cries out for a remake (though tragically I’m sure remaking an obscure 90s horror game with mediocre sales isn’t likely, even given Realms’ critical acclaim). Frictional Games’ HPL engine would be perfect, I think, though I’m sure there are other choices that would also work well. Even with the dated graphics and gameplay, however, the game still has a great deal of character. I’m thinking of picking up Clive Barker’s Undying, which somehow I still haven’t played, in hopes of finding something that scratches the same itch (apparently, Undying suffered from exactly the same problem as Realms: strong critical acclaim, terrible sales). What I’d really like to see is a modern game that combines the panic, dread, and visceral affective potency of recent survival horror offerings with the baroque storytelling style and weird atmosphere of Realms of the Haunting; if anyone knows of something that fits that bill, let me know!

Christopher Nightingale

Thank you for writing this article, it’s been one of the better explorations of the aged classic ROTH. Did you ever find any other media, game or books similar to ROTH?

I’ve had a similar experience with the game, and have since been looking for similar stories in books and media. House On The Borderlands was similar in its cosmic tone.

Thank you

Bearded-Devil

Sorry for the long delay on the reply here.

In terms of other works with ROTH vibes, there’s nothing that exactly hits the feeling it produces, but I will say that I’ve been playing Pathologic 2 recently, and it’s not totally far off. It’s an incredibly strange, often bleak experience, like a surreal Russian novel. There are some technical oddities (rather like ROTH in that regard) but it looks quite beautiful, and the story is rich, dark, saturated with a sense of vague otherworldliness. It is slow and can be frustrating, it’s not “fun” in the traditional sense of the word, but it’s pretty wonderful.

For a more classic Haunted House type thing that feels a little ROTH-adjacent, Resident Evil 7 actually isn’t that far off, albeit with a Southern Gothic flavour.

For books, nothing really precisely captures it, but both The Haunting of Hill House and House of Leaves could be worth a look.