A few words on the design and general “philosophy” of Hexenburg. While the Castle is sprawling, much of it is empty. What monsters there are in the ruin, however, tend to be quite dangerous for a low-level party. The idea is to use a few powerful monsters to their greatest effect, rather than cramming every room with lots of weak monsters. There are a few exceptions to this (the Goblin tribe in the Dungeons, or the hordes of undead in the Catacombs), but largely the Castle should feel big and mostly empty. This is to encourage a feeling of paranoia and uncertainty amongst the players. As they enter each room, they should feel uncertain what they’re going to find. Each encounter should be a dangerous one where the stakes feel high, not a run-of-the-mill hackfest where the players mow through squads of monsters with relative ease. Play monsters intelligently; they should employ clever tactics against players, using special attacks, dirty tricks, spells, terrain, disarming attacks, and the like. They should retreat when wounded, rather than fighting to the death.

Hexenburg is a cursed place – a place where evil and darkness hold saw. Dead bodies allowed to lay on the grounds can spontaneously reanimate, and the very stones of the place seem to whisper black obscenities on those who tread upon them.

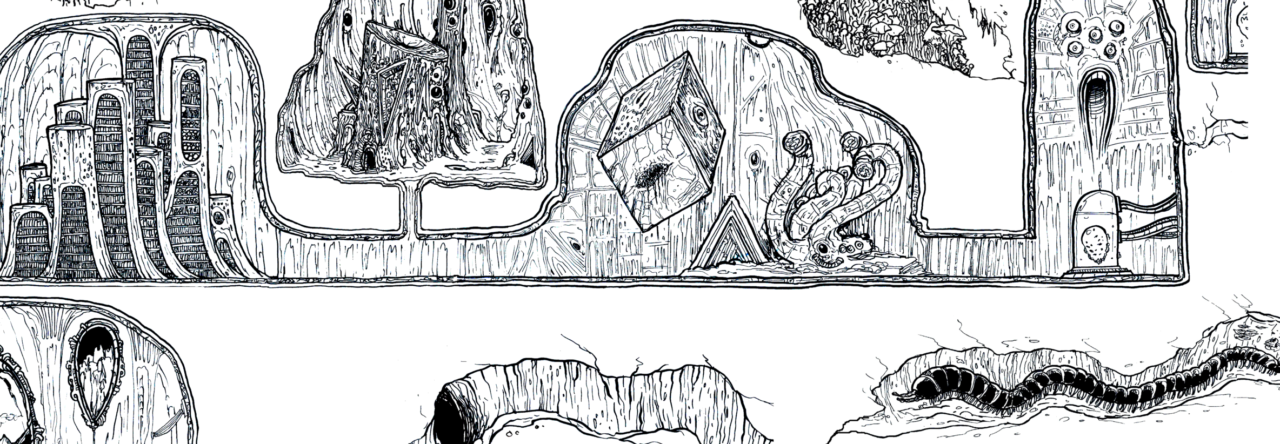

As an incipient blizzard swirls around you, Hexenburg Castle at last comes into view: a foreboding mass of dark stone, half-reclaimed by the forest. The trees in this part of the forest seem sickly, tree-trunks mottled by blight, scabrous bark peeling. The path winds up the raised earthwork motte of the fortress, then passes over a rickety old drawbridge spanning a snow-clotted ditch. Old wooden spikes are visible in this moat, to deter any trying to scale the walls. The crenellated battlements are beginning to sag and crumble but the gatehouse is still mostly intact. Past the walls rise several towers – two largely intact, one a broken stub – and a formidable keep. Rotting mangonels are visible on the walls.

Perception DC 20 to notice a light flicker in the window of the west tower. DC 15 to notice:

Scattered on the path leading up to the castle are a number of bones, broken weapons, cloven shields, and other remnants of an old battle – likely the very battle that resulted in the castle’s ruination at the hands of marauders from the north.

A thorough search of the battlefield produces a masterwork longsword.

Watchtower Table

There are many watchtowers in Hexenburg Castle, which may or may not be searched by the players. The following table allows for random generation of watchtower contents. Each tower has 4 levels and thus four randomized rooms. Roll on the following table if the players decide to go poking out in a watchtower:

| Roll d% | Result |

| 1 | A room covered in old bloodstains. |

| 2 | A room covered in fresh bloodstains. |

| 3 | Four Goblins hunting rats for stew, led by a Goblin Ranger. |

| 4 | A heap of human bones. |

| 5 | Aklo runes scrawled on a wall in blood (random 1st level Necromantic spell formulae if deciphered with a DC 20 Linguistics check). |

| 6 | Sleeping bats (they could form a swarm if threatened). |

| 7 | A human corpse nailed to a wall, with its tongue and fingernails removed. |

| 8 | A human corpse nailed to the floor with its heart, liver, lungs, and brain removed. |

| 9 | A room with dozens of Elf ears nailed to the walls. |

| 10 | Torture implements – a rack, thumbscrews, and branding irons. |

| 11 | A roosting Owlbear in its nest. |

| 12 | A severed head in the middle of the room with black gems (25 gp each) replacing its eyes. |

| 13 | Lectern with a book in an unknown language. |

| 14 | Lectern with a Vacuous Grimoire which appears to be a treatise on Hexenburg’s history. |

| 15 | A telescope and other astrological equipment. It looks remarkably new. |

| 16 | An Ettercap lair filled with webs and web-swathed corpses. |

| 17 | Empty coffin. |

| 18 | Coffin full of congealing blood. |

| 19 | A huge pile of human teeth. |

| 20 | A very large cocoon. |

| 21 | Chalk instructions for summoning a Chaos Beast (counts as Planar Binding, but only for Chaos Beasts). |

| 22 | A large basin of stagnant water full of leeches. |

| 23 | Assassin vine. |

| 24 | A black goat, staring at you. |

| 25 | Suicide-inducing statuette; a corpse dangles from the rafters, tongue and eyes bulging. Will DC 10 to resist. |

| 26 | An armoury with a morningstar, bec de corbin, bardiche, and handaxe. |

| 27 | Slime Mold. |

| 28 | Cursed but empty room that generates violent and evil thoughts in those who enter. |

| 29 | Wooden crates full of human body parts, carefully sorted. |

| 30 | Puzzle-box containing a random Kyton; Disable Device DC 20 to open. |

| 31 | Crawling hand. |

| 32 | 8 Crawling hands. |

| 33 | Squatting leper. |

| 34 | 3 Shriekers. |

| 35 | A large owl, possibly friendly, possibly aloof. |

| 36 | A map of the Catacombs scrawled in red chalk. |

| 37 | 1d12 Stirges. |

| 38 | An armoury with two suits of chainmail and one suit of masterwork splint mail. |

| 39 | Dead body with a Demonic Cyst (see L6) growing out of it. |

| 40 | Cow bones. |

| 41 | Goat bones. |

| 42 | Wolf bones engraved with mystic runes and arranged in an uncanny design. |

| 43 | Nest of 2d6 giant ticks. |

| 44 | Magical circle carved into the stones. If filled with blood it teleports those inside it to another watch-tower with an identical circle. |

| 45 | Mucus trails leading into the castle walls. |

| 46 | Shelves with 4 jars of lamp oil (1 pint each), a hooded lantern, and a spare dozen torches. |

| 47 | The husks of many, many insects. |

| 48 | Shed grick-skin. |

| 49 | Dozens of empty and broken bottles. |

| 50 | Huge heap of burlap sacks and bags, one of which is a Bag of Holding, another of which is a Bag of Devouring. |

| 51 | Extremely drunk Dwarf named Mim who’s not sure where he is or how he got there. He’s a 2nd level Barbarian. |

| 52 | Mimic. |

| 53 | Rat’s nest containing 256 sp, 452 cp, and 22 gp. |

| 54 | Mangonel stones (as in G12). |

| 55 | Mangonel parts (as in G11). |

| 56 | An armoury with 12 longspears and 4 glaives. |

| 57 | Raven’s rookery containing 78 sp, 12 gp, and 188 cp, plus a pair of gold earrings worth 50 gp. |

| 58 | An Allip. |

| 59 | Barrels of sour wine (vinegar, essentially). |

| 60 | Dozens of broken crates. |

| 61 | Two large, feral black cats. |

| 62 | One hundred human tongues in a cauldron. |

| 63 | The lingering sound of a child crying, but nothing else. |

| 64 | Fungus that’s strangely shaped itself into the visage of Saint Severine. |

| 65 | A heap of empty buckets crawling with woodlice. |

| 66 | Three large nets. |

| 67 | An outlaw guilty of two murders and theft. He lacks combat gear beyond a dagger, but does have a purse with 23 platinum pieces and 43 gp. |

| 68 | A pile of partially burnt holy texts. |

| 69 | A statue of St. Bastiana which weeps blood and grants an Aid spell (20th level) to those of the faithful who pray at it, but smites heathens who pray at it as per Inflict Light Wounds (1d8+5, DC 16 for half). |

| 70 | Scorch marks and the remnants of burnt furniture. |

| 71 | Empty cages made of wicker. |

| 72 | Crumbling floor; unless a character has Trapspotter or Stonecunning, they don’t get a Perception check automatically; it’s DC 20 to detect otherwise. The hazard requires a Reflex DC 20 to avoid and deals 2d6 falling damage, depositing characters in the room below. |

| 73 | Signs of a recently made camp. |

| 74 | The skeletal remains of a marauder, armed with a broken battleaxe and hide armour. |

| 75 | A child’s doll. |

| 76 | Firewood, somewhat damp but still useable. |

| 77 | An empty wooden chest. |

| 78 | A trapped steel chest (Perception DC 20, Disable Device DC 20 – needle with Greenblood Oil, Fort DC 13, 1 Con damage, 1/round for 4 rounds, 1 save cures), locked (DC 20 to open). Inside is a +1 Heavy Mace made of dark metal that fills a character with feelings of intense pleasure when used to kill. |

| 79 | Rotten timber. |

| 80 | A lost Black Dragon hatchling. Will be helpful to Chaotic Evil characters, friendly to Chaotic or Evil characters, indifferent to Neutral characters, unfriendly to Good or Lawful characters, and Hostile to Lawful Good characters. If befriended, its mother will eventually come looking for it. |

| 81 | Barrels of crossbow bolts (300). |

| 82 | A powerful Necromancer named Markus Gor, casually scratching runes into a bandit’s corpse. |

| 83 | Dead body with organs liquefied, containing a clutch of Tentamort eggs. |

| 84 | A broken masterwork greatsword (notched and bloodstained) hanging on the wall. |

| 85 | Rotting tapestries depicting scenes from the Winter Crusades. |

| 86 | A small shrine dedicated to a wolf-god, with wolf-pelts everywhere and a wolf’s head on an altar. |

| 87 | A pair of runaway peasant children from Gründorf, now very lost and very scared. |

| 88 | Dead leaves and twigs, heaped into a nest, with no sign of its owner. |

| 89 | A Gargoyle. It will pretend to be a statue, but will then start following the party around when they aren’t watching. |

| 90 | Goblin lookout. |

| 91 | Berserking Greatsword hung on a wall, along with two bastard swords, four longswords, and six shortswords. |

| 92 | Malevolent Faun playing pan-pipes on the window ledge. |

| 93 | Pornographic graffiti, probably drawn by a bored Goblin lookout. |

| 94 | Rusted caltrops everywhere. |

| 95 | Empty shelves. |

| 96 | Buckets of small stones for murder holes. |

| 97 | Two dead Goblins wrapped in cobwebs. |

| 98 | A Halfling tomb-robber named Hippolyta here to plunder the chapel’s catacombs. |

| 99 | Tentamort. |

| 100 | Small table upon which can be found a leather pouch containing a Deck of Many Things. |

In a pinch, the above table can be used for any random castle/dungeon rooms required, for whatever reason.